While I will always encourage reading full ancestor narratives, I understand some may prefer a quicker read. Click the button below to visit Hannah’s blog, an abbreviated version of her story.

This is the Record They Didn’t Keep

St. Louis, 1898. A woman lies dying. Her husband? Gone. Vanished decades earlier. Some say he died. Others say he walked away. But a year after her death, a man matching his name, age, birthplace, and citizenship lands quietly in Philadelphia, returning from England. His name is Edmund Holdsworth, and he just might be Hannah’s long-lost husband.

This is the story of Hannah Risby Holdsworth, a mother, a migrant, a midwife, and possibly the wife of a man who disappeared without a trace.

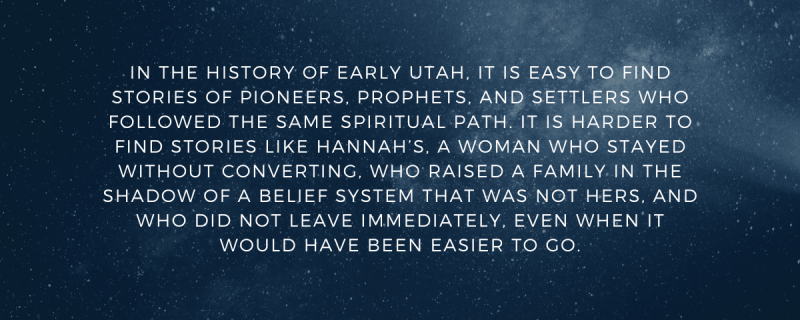

I’m telling Hannah’s story not because she made headlines, but because she didn’t. She’s one of countless women history overlooked. Women whose names were left out or misunderstood. Women who endured, worked, raised children, and kept going without recognition, without applause.

Hannah’s strength wasn’t loud. It was steady. It mattered.

As for her husband? Someone with his name returned years too late, and with questions no one could answer.

Make no mistake, this story belongs to Hannah.

He’ll get his time to shine.

First, we remember Hannah Risby Holdsworth.

1828 - Her Life Began Between Prayers and Poverty

Hannah was born on October 14, 1828, in Horsley, Gloucestershire, England, to George Risby and Hannah Haywood. She was baptized on December 28, 1828, not in her family’s home parish of Horsley, but in Dursley, at a Wesleyan Methodist chapel [1].

This wasn’t unusual for the Risbys. George and Hannah’s other children were baptized as Wesleyans too, pointing to a family grounded in nonconformist faith, choosing Methodism over the dominant Church of England.

Why Dursley? It was a bustling market town about six miles from Horsley, a reasonable journey by foot or cart. It had a registered Wesleyan chapel, unlike Horsley, and George, a traveling merchant, may have passed through regularly for business. The choice reflects both religious conviction and practical connection: faith shaped their beliefs, but the road shaped their decisions.

Still, by the late 1830s, Horsley was in crisis. The once-thriving cottage weaving industry had been hollowed out by factory-made textiles. Common lands were being enclosed, cutting off access to resources families had relied on for generations. Wages vanished. Food became more expensive. Families who had once made a modest living were now simply trying to survive.

Modern Day Horsley

Even George, with the relative freedom of his work as a merchant [2], would have felt the strain. He may have spent more time on the road, bartering and selling in neighboring towns just to keep food on the table. His ability to move through rural Gloucestershire was a temporary advantage, but not a solution.

In 1838, one of Hannah’s sisters, Rhoda Risby, just 13 years old, was convicted of “damaging beech trees, property of Mr. Young, in the Parish of Horsley.” Her sentence: 14 days of hard labor and a fine [3]. Beech trees were a valuable source of fuel and timber, and for struggling families, they also represented warmth, income, or a way to make it through the winter.

1841-1851 - The Hills Were Quiet. The Mills Were Not

Sometime before 1841, the Risbys left Horsley. George may have used his trade routes to scout out a new future, and Bristol, with its booming factories and constant demand for labor, offered something Horsley no longer could: a wage, however small, and the possibility of stability.

By 1841, the Risby family had left the hills of Horsley for the industrial sprawl of St Philip and St Jacob, a hard-edged working-class parish in Bristol [2]. Horsley, once known for cottage-based weaving, was fading fast. As industrial looms replaced handwork and local demand shrank, so did opportunities. For cotton weavers like the Risbys, the city offered one thing the countryside couldn’t: a wage.

That wage came with a cost.

Bristol in the mid-19th century was a city of coal smoke, overcrowded housing, and relentless labor. Factories dominated the landscape, and every working-class family lived in their shadow. Thirteen-year-old Hannah Risby, listed as “Anna” in the 1841 census, was already at work as a cotton weaver, alongside her parents and three sisters. Childhood ended early here. Everyone worked. Everyone was needed.

By 1851, 22-year-old Hannah was still living at home, now working as a shoe binder, a job requiring precision, strength, and sore fingers [4]. Her father George Risby and mother Hannah Haywood Risby were both listed on the census as “cotton workers” [4]. That likely meant one thing: they worked at the Great Western Cotton Company, the only major cotton mill in Bristol at the time and one of the city's largest industrial employers. For a family in their position, there were few other ways to earn a living.

Located just a mile from their home, the Great Western Cotton Company was one of the largest mills in Bristol and among the most grueling. Opened in 1838 and powered by steam engines, the mill consumed raw cotton shipped in from the U.S. South and turned it into thread and fabric for Britain’s booming textile markets. It was a monument to industrial progress and a house of physical toll.

Workers labored 12 to 14 hours a day, six days a week. The noise inside was deafening. Machines ran continuously, with little to no safety measures. Hair and clothing could get caught in the moving gears; fingers were easily crushed. Cotton dust filled the air, causing chronic lung problems like byssinosis, known as "mill fever" or “Monday fever.” Lighting was poor. Airflow was worse.

Beneath the grind of daily labor, something was shifting. By the early 1850s, unrest was brewing inside the walls of the Great Western Cotton Company, especially among its women workers. Conditions weren’t just exhausting; they were unjust. Eventually, the women and girls pushed back:

Source: Mike Richardson, "The Maltreated and the Malcontents: Working in the Great Western Cotton Factory 1838-1914," History Workshop, 27 June 2023, www.historyworkshop.org.uk/activism-solidarity/the-maltreated-and-the-malcontents-working-in-the-great-western-cotton-factory-1838-1914.

The Risbys had a decision to make: to stay and endure, or to risk everything for a future across the Atlantic.

They had survived economic collapse in Horsley and the grinding machinery of Bristol’s mills, but even survival had its limits. The promise of steady wages was never enough to escape the cycle of poverty. As unrest stirred among working women and the toll of factory life deepened, the dream of America, distant, uncertain, but full of possibility, began to hold weight.

Leaving meant abandoning familiarity, kin, and everything they had known. However, staying meant more of the same: long hours, poor health, no voice, and little chance to break the generational pattern. For families like the Risbys, emigration was not just about chasing opportunity. It was about escaping exhaustion.

Sometime in the early 1850s, they chose movement over stagnation. Not because it was easy, but because it was the only way forward.

Hannah's journey was just beginning.

1853-1854- A Marriage, A Funeral, A City That Didn’t Wait

In 1853, the Risbys left England behind. George and Hannah Risby, along with their daughters Hannah and Eliza, boarded the Warbler in Liverpool and arrived in New Orleans on December 23, 1853 [5].

From there, they traveled north, likely by steamboat, up the Mississippi River to St. Louis. This was the most common inland route for immigrants arriving through New Orleans, offering passage into the expanding interior of the United States. The journey would have taken several days, sometimes longer depending on the river’s conditions and the steamboat’s speed.

St. Louis in 1846, Henry Lewis, St. Louis Art Museum

Why St. Louis?

St. Louis in the 1850s was a city in flux, booming with commerce, industry, and immigration. It sat at the crossroads of east and west, a launch point for settlers moving toward Kansas, Nebraska, and the territories beyond. Its streets echoed with dozens of languages. German, Irish, and English migrants formed their own enclaves. And in the center of it all, the city buzzed with opportunity and risk.

It may have been exactly what the Risbys were looking for: a place where George could continue his trade as a merchant, and where labor was always in demand. There were mills, riverfront warehouses, cobblers and binders, and a busy domestic labor market for women.

Somewhere in that first year, Hannah met Edmund Holdsworth.

Like Hannah, Edmund was an English immigrant, and it is possible they met through expatriate networks in St. Louis, which were growing rapidly during this period. English newcomers often sought out familiar accents, customs, or work connections in a city crowded with strangers. By 1854, both were living in St. Louis, and their paths crossed.

On December 15, 1854, Hannah married Edmund Holdsworth in St. Louis. The ceremony was performed by Milo Ardus, a Mormon elder [6]. Three days later, on December 18, her father George Risby died [7].

Whether it was a love match, a marriage of convenience, or even a father’s last wish, we may never know. What we do know is that it happened quickly, during a time of upheaval and transition.

A marriage and a death, just days apart. A beginning and an end in the same week. Hannah had barely set roots in this new world before she had to bury the man who brought her to it.

1856 - Utah Territory: She Carried the Fire, Not the Faith

By 1856, Edmund and Hannah Holdsworth were living in Utah Territory, with records placing them in both Weber County and Provo City [8]. Like many others, they had crossed oceans and plains in search of something new: stability, opportunity, perhaps even a spiritual home. What they found was a land shaped by a faith Hannah never embraced.

Utah was still young. The territory had been established only a few years earlier, and its early settlements were defined by hard labor, communal ideals, and an overwhelming sense of spiritual purpose. For Hannah, who never joined the LDS Church, life there likely felt more complicated.

She was married to a man with deep ties to Mormonism. Edmund had been baptized into the Church in England back in 1845. He believed in the mission, in the promise of Zion, and he brought his wife and children to a place where that belief was everything.

Hannah stayed on the outside. She never converted. Not then. Not later. Not ever.

In a society where religion shaped access to resources, relationships, and trust, Hannah would have lived on the edges of full belonging. She may have joined neighbors for harvests, for births, for funerals, but always at arm’s length. Her daily life would have been defined not just by labor and weather, but by subtle social exclusion.

The work was hard. The terrain was harder. She cooked over fire. Hauled water. Raised young children in a place with limited medical care, few legal protections for women, and strict religious norms. Through it all, she found a way to keep going.

She gave birth to two of her children in Utah, far from her family, far from familiarity. There were no safety nets, only strength, and whatever support she could find in a community whose faith she did not share.

No sermons. No script. Just quiet endurance.

She planted gardens in rocky soil. She stitched clothing. She likely midwifed other women’s births. In every act of care, she carved out space for herself, not within the faith of her neighbors, but alongside it, in the sliver of independence she could still claim.

She did not follow the dominant path. She built one just beside it.

1858-1860- Leaving Utah, Landing in Illinois

The Holdsworths left Utah sometime between the birth of their second son, William, in Utah (circa 1858), and the birth of George in Illinois in 1860 [9]. By the time of the 1860 Census, they were living in Township 7 Range 8, Macoupin County, Illinois [9]. Their three sons, Albert (4), William (2), and George (5 months), were listed alongside them [9]. Edmund appears as a laborer with $300 in real estate and $200 in personal estate, a modest but stable footing [9].

It was a quiet departure, but a complicated one.

Edmund appears to have remained a practicing member of the LDS Church. He had chosen to settle in Utah, the heart of the Mormon faith, and raised his children in its sphere of belief. However, Hannah never joined the Church. That difference, subtle at first, may have become harder to navigate as their family grew and the pressures of conformity deepened.

Their relocation from Utah to Illinois during this period may have been influenced by several factors. The late 1850s were marked by the Utah War, a conflict between Mormon settlers and the U.S. government, which created an atmosphere of uncertainty and tension in the Utah Territory. Some families, seeking stability and safety, chose to leave the area. Macoupin County, with its fertile farmland and growing communities, offered economic opportunities and a chance for a fresh start. The county's location between St. Louis and Springfield provided access to markets and transportation, which could have been appealing to families looking to establish themselves in a more secure environment.

By late 1860, the Holdsworths' moved to St. Louis. The Holdsworths' move from rural Macoupin County to the bustling city of St. Louis in the early 1860s likely stemmed from a desire for greater economic opportunity and community support. While Macoupin County offered a stable agricultural environment, its limited economic prospects may have prompted the family to seek better opportunities. St. Louis, rapidly industrializing and expanding, presented a vibrant urban setting with diverse employment options, particularly in manufacturing and transportation sectors. Additionally, the city's growing population and established communities could have provided the Holdsworths with a more dynamic social environment and access to amenities not available in their previous rural setting. The move to St. Louis thus represented a strategic decision to improve their economic standing and quality of life.

1863-1864 - Faith, Family, and a Woman Alone

In November 1860, Edmund Holdsworth was officially naturalized in St. Louis [10]. Three years later, he appears again, this time on a Union draft roll in July 1863 [11]. In 1864, he is listed in the St. Louis City Directory as a laborer, residing on Buchanan Street between 10th and 11th [12].

Given his return to St. Louis in 1860 and his naturalization process, it is reasonable to assume that Hannah and their children were living with him at the time.

But after that 1864 listing?

Nothing.

No death record.

No probate.

No obituary.

No Civil War file.

No property sale.

No LDS records.

He did not die in battle.

He did not leave a legal trail.

He did not come back.

He simply vanished, leaving Hannah a single mother.

1864 - Children Were Claimed by Another Faith. She Stayed Whole.

The next surviving record is not about Edmund. It is about the children. On January 14, 1864, in the middle of a brutal St. Louis winter, Hannah’s three sons, Albert E., William H., and George F. Holdsworth, were baptized into the Catholic Church at St. Malachy Parish. Each boy was listed as coming from “the Poor House” [12]. This was not a quiet family conversion. It was a crisis.

To appear in the baptismal register so early in the year, the boys had likely been admitted to the Poor House in late 1863, suggesting that something serious and sudden happened just months after Edmund’s last confirmed presence in the city. He does appear in the 1864 St. Louis City Directory, listed as a laborer on Buchanan Street [12]. But that entry is misleading. City directories were compiled using information gathered months in advance, usually in the summer or fall of the previous year. So while Edmund may have still been in St. Louis in mid to late 1863, by the time the directory was printed in early 1864, he may have already vanished.

A likely catalyst emerges just a few months earlier: Edmund’s name appears on a Union Army draft roll in July 1863. The federal draft that summer sparked confusion and fear across the country, especially among immigrants and laborers who could not afford to pay their way out. For a man like Edmund, the options were grim: enlist, flee, or vanish. The commutation fee, $300 to legally avoid service by paying for a substitute, was far beyond the reach of most working-class men. That sum would be equivalent to over $7,000 today [13]. That draft record may mark the moment everything fell apart.

While the draft is a plausible explanation, other possibilities exist. He may have succumbed to illness or injury, with his death unrecorded due to the chaotic wartime conditions. Alternatively, he could have deserted his family, either to avoid military service or to start anew elsewhere. The social and economic upheaval of the Civil War era created an environment where individuals could vanish without a trace, their fates obscured by the chaos of the times. In this tumultuous landscape, Edmund's disappearance becomes one of countless unresolved stories, leaving behind only fragments and unanswered questions.

Edmund’s disappearance left Hannah with no support, no income, and four children, one of them still an infant. The Catholic baptism of her sons was likely a procedural act. Catholic institutions often baptized children in their care, regardless of religious background, particularly if they were housed long-term or being placed with Catholic families. For the Holdsworth boys, this was not about belief. It was about access to shelter, food, and basic safety.

Hannah herself would not have been eligible for admission. Catholic orphanages were rigidly structured: boys, girls, and adults were housed separately, often in entirely different institutions run by different religious orders. A mother, especially one without illness or documented disability, would not have been allowed to stay with her children in a facility designed for boys. Her separation from them was not necessarily voluntary. It was institutionally enforced.

As for Lizzie, her fate in those early months is unknown. She may have remained with Hannah. She may have been placed in a separate Catholic girls’ orphanage, lost to time in a parallel system that rarely linked sibling records. No documentation of her placement has surfaced.

Why would a mother like Hannah place her children in an orphanage?

There is no surviving letter, no diary entry explaining her decision. However, the context speaks volumes. In the absence of answers, we can only piece together the possibilities: what she faced, what she feared, and what may have driven her to entrust her sons to institutional care.

Here are five reasons Hannah may have felt she had no other choice. Click the arrows to the right for more details.

This separation wasn’t a failure. It was a sacrifice, one born of desperation, strategy, and a mother’s refusal to let her children starve on her watch.

Somewhere in St. Louis, in a city full of rules and records that rarely accounted for women like her, Hannah started over.

1864-1870 - Hannah? She Wasn’t the One Who Left

What we do know is that Hannah was left on her own, likely searching for housing, food, and the means to get her children back. She may have slept in boarding houses, relied on temporary charity, or worked odd jobs just to stay afloat. This was the brutal calculus of abandonment in a city where women like Hannah were offered survival, but not support.

On August 14, 1864, just seven months after her sons were baptized into the Catholic Church, Hannah Holdsworth took a step of her own. She was baptized into the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (RLDS) [15].

To some, it might seem like a contradiction. This was a woman who had spent years resisting the LDS Church. She had lived in Utah. She had been married to a Mormon. Yet, she had not followed him fully into that faith. Not when he left the Methodist roots she was raised in. Not when he took on church titles. Not when the pressures of that movement came crashing into their family.

So why now?

This was not a theological about-face. This was not a revelation in the night. This was something more human. More practical, possibly more desperate.

The RLDS Church was not the same as the Utah-based LDS Church Edmund had once embraced. The RLDS rejected polygamy and the authoritarian structure of Brigham Young's leadership. It offered a more moderate, more familiar, and more emotionally accessible version of the faith Edmund had dragged her into.

Perhaps, more importantly, it offered community. It offered relief. It offered someone who might have understood what she had just endured: abandonment, poverty, the heartbreak of parting with her children, and the uncertain limbo of not knowing if her husband was dead or simply gone.

Her baptism into the RLDS may not have been about doctrine. It may have been about survival. About reclaiming something, anything, that could still give her a place to belong.

1870s - The Years That Made Her, Quietly

By the early 1870s, Hannah Holdsworth had survived everything the last decade could throw at her: abandonment, poverty, the institutional separation from her children, religious isolation, and near invisibility in the historical record.

Her story did not end there.

On August 1, 1868, two of her sons, Albert and William, were baptized into the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (RLDS) [15]. This is the first sign that the family may have been reunited. These baptisms did not happen in an orphanage. They happened in a church community where Hannah herself had joined just four years earlier.

By the 1870 U.S. Census, the reunion is no longer just a possibility, it is a fact. Hannah is living in St. Louis with all three of her sons: Albert, William, and George. For the first time, her daughter Lizzie appears too [16]. The family is back together.

There is no record of how it happened. no explanation of who intervened, or what circumstances allowed it. Somehow, after years of separation, Hannah managed to reclaim her children and rebuild a home.

And in 1873, she reappears again. Not as a dependent. Not as someone’s wife.

She appears under her own name: Hannah Holdsworth – Midwife [17]. It is a quiet line in a city directory, but it speaks volumes. After years of being sidelined by circumstance, this was a declaration of self. She had made herself visible again.

In 19th-century St. Louis, “midwife” wasn’t a decorative title. It meant skill, community trust, and a reputation earned through experience. Midwives were more than birth attendants. They were nurses, healers, grief-holders, and often the only medical practitioners available to working-class and immigrant women.

For a woman who had once been forced to place her children into institutional care, this role was nothing short of revolutionary. It placed her back in the center of community life, not as a burden, but as a caretaker.

But after 1873, her occupation disappears from public record. That doesn’t mean she stopped working. It means the work she did returned to the shadows, unpaid, undocumented, but still vital. Like so many women of her class and time, her labor slipped into the spaces society didn’t bother to write down.

1880-1887 - Still No Widow

Even as she built herself back up, Hannah never identified herself as a widow. Not in 1873. Not in the 1880 census, where she’s listed as “single,” living with her adult sons Albert and William [18].

Her third son, George, had died by that point. Her daughter, Lizzie, was still missing from the record—her fate uncertain, her trail cold.

The house she lived in was modest, rented, and tucked into South St. Louis. It was hers.

Based on surviving records, one of the most striking aspects of Hannah’s story is her enduring silence about Edmund. For more than twenty years after his disappearance, she never publicly identified herself as a widow. Perhaps it was legal caution. There was no death certificate, no confirmation. It may also have been emotional: a quiet refusal to declare an ending she never truly received.

1887 -The Widow Appears

By the early 1880s, Hannah Holdsworth had spent nearly two decades as a single woman, raising her surviving sons, working as a midwife, and maintaining a quiet presence in South St. Louis. She had endured economic collapse, religious exile, and the institutional separation of her children, yet she had never once called herself a widow.

There is no surviving death record for Edmund. No letter. No newspaper notice. Nothing to suggest she had learned something new. Why, after all this time, did she finally adopt the title? Maybe she was simply ready. Maybe she had waited long enough. Or maybe the weight of the unknown had finally become too heavy to keep carrying. Whatever the reason, this quiet shift in how she named herself was the only official acknowledgment she ever gave that her husband was truly gone.

It is important to note that while St. Louis city directories were published annually after 1865, their content varied, and some editions may be missing or incomplete. Therefore, it is possible that Hannah may have identified as a widow earlier than 1887, but such information might not have been recorded or preserved in the available directories.

1888-1898 - A Home of Her Own: Life on Flyer Avenue

By the late 1880s, Hannah Holdsworth had settled at 4342 Fyler Avenue, a modest address in South St. Louis, not far from where she had spent the past two decades rebuilding her life. The neighborhood, situated on the growing southern fringe of the city, was filled with brick row houses, corner shops, saloons, and churches. It was not affluent, but it was stable. Working-class families filled the blocks: German and Irish immigrants, Black Missourians, and others like Hannah, English-born, long-resident, and quiet in their survival.

By 1890, the city had begun to encroach. The smell of coal smoke hung in the air. Streetcars clattered up nearby Morganford Road. Children played in alleys. Wash lines stretched across small backyards. Somewhere in the middle of it all, Hannah lived out her final years.

By the time she settled on Fyler Avenue, her world was shaped more by corner grocers and coal deliveries than by church gatherings. Her neighbors were mostly Catholic and Protestant, rooted in parishes that served the city's immigrant working class. It is likely that Hannah’s relationship with faith, once a matter of strategy and survival, had returned to something quieter, personal, private, and unrecorded.

Modern Day Location for 4342 Fyler Avenue

The house itself is gone now, razed in the waves of mid-20th-century urban renewal, but its meaning endures. Fyler Avenue was no poorhouse. It wasn’t an orphanage. It wasn’t borrowed shelter. It was hers.

Maybe she still practiced midwifery behind closed doors. Maybe she took in laundry, or helped neighbors with births, illnesses, or small domestic catastrophes. There are no records of that labor, but it would have been expected of a woman like Hannah: the reliable widow next door, the one who had quietly outlived so much.

There is no surviving written account of Hannah. Just this address. 4342 Fyler Avenue tells us what no document ever did:

She overcame so many obstacles but she made it.

That after decades of hardship and loss, she died with a roof over her head, her name in the records, and her adult sons by her side. In 1898, the state recorded her death. Her occupation? “Housewife” [20].

What She Lived Through

Hannah Holdsworth's life in St. Louis was a testament to resilience amid a city undergoing relentless transformation. Arriving in an era illuminated by oil lamps and traversed by horse-drawn carriages, she witnessed the city's evolution into a hub of industrial progress. Gaslights gave way to electric bulbs, streetcars replaced carriages, and bridges like the Eads Bridge, completed in 1874, connected the city across the Mississippi River. The emergence of silent films and the earliest automobiles marked the dawn of a new century.

Throughout these changes, Hannah endured personal trials that mirrored the city's own upheavals. She lived through the Civil War, faced poverty, and bore the weight of raising her children alone after her husband's disappearance. The 1877 general strike in St. Louis, part of the wider Great Railroad Strike, underscored the city's labor unrest and economic challenges .

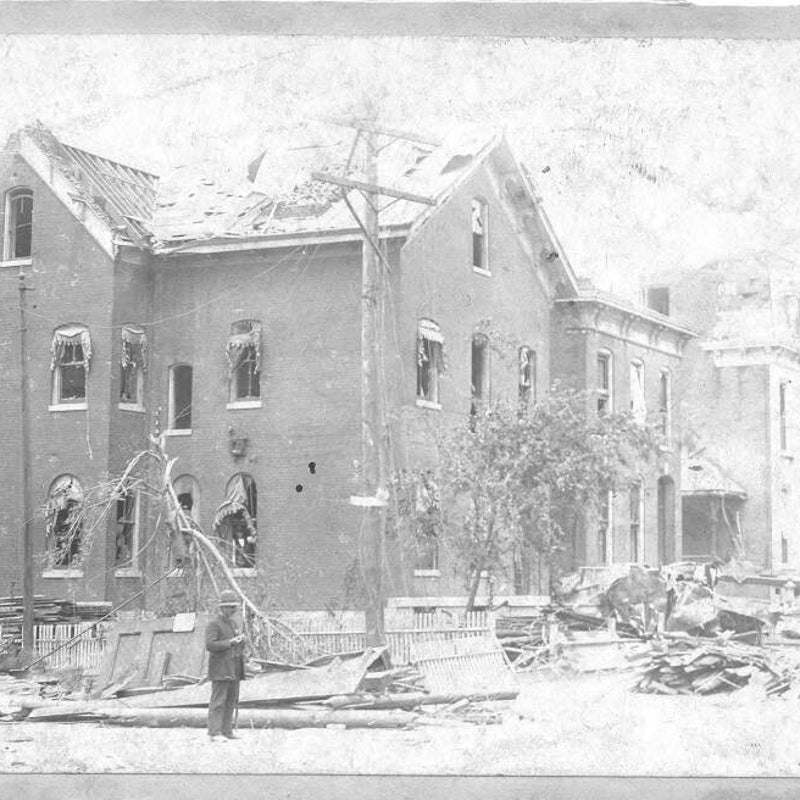

In 1896, St. Louis was struck by one of the deadliest tornadoes in U.S. history. On May 27, a massive storm tore through the city, destroying homes, businesses, and entire neighborhoods. Over 250 people were killed, and thousands were injured or displaced. The destruction was widespread—and deeply personal for those who lived through it.

Source: St. Louis Public Library Digital Collections

Hannah Risby Holdsworth was living on Flyer Avenue at the time, safely outside the tornado’s destructive path. In a city like St. Louis, even those untouched by the winds felt the weight of the aftermath. However, she would have seen the headlines, heard the stories, and perhaps opened her door to neighbors with missing family or lost homes. The city was grieving, and Hannah, no stranger to loss or hardship, likely found ways to help.

Even though her home was spared, Hannah likely stood among the many who helped St. Louis begin to heal, not with grand gestures, but with the same steady strength that had carried her through decades of uncertainty. Given what we know of Hannah’s life, her resilience, her experience with hardship, her work as a midwife, it’s easy to imagine her stepping in to help. She would have known how to tend wounds, calm frightened children, and organize care when institutions fell apart. Recovery wasn’t just about rebuilding homes; it was about tending to the living. Hannah may have offered comfort to neighbors, supported families who had lost loved ones, or simply helped put one foot in front of the other.

She watched as St. Louis expanded and modernized, yet she remained rooted, a constant in a city of change.

At the End of It All

Hannah Holdsworth died on September 21, 1898, at her home on Flyer Avenue, surrounded by a life reclaimed.

A modest house.

Adult children who came home.

A community who showed up to mourn her.

Her obituary, published by the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, quietly marked the moment, noting her decades-long connection to the faith and the esteem she carried in death.

We See Her Now

We began this story with a blurry image of Hannah, a name in a record, a faint outline in the margins of someone else’s life. But across pages, maps, and memories, she came into focus. Not just as someone’s wife or someone’s mother, but as her own person.

Now, at the end, we don’t have to guess at who she was. We see her now in color and in full, where she always belonged.

And something tells us this won’t be the last time her name is spoken.

She endured with nothing but her name.

Edmund escaped with everything but his.

Edmund paused the story. We are pressing play.

His story is up next.

Citations

[1] The National Archives of the UK (RG 4; Piece 615).

[2] 1841 England Census.

[3] Gloucestershire Archives, Q/Gh/10/2.

[4] 1851 England Census.

[5] National Archives (Passenger List of the Warbler).

[6] Missouri Marriage Records (1854).

[7] Missouri Death Records (1854).

[8] Utah State Archives, Census and Substitutes Index.

[9] 1860 U.S. Census, Macoupin County, IL.

[10] Missouri Naturalizations, 1802–1956.

[11] NARA, Civil War Draft Registration Records (1863).

[12] 1864 St. Louis City Directory.

[13] Draft commutation fee inflation estimate: CPI Inflation Calculator.

[14] RLDS Membership Records.

[15] FamilySearch, Image 18 of 169.

[16] 1870 U.S. Census.

[17] Gould’s St. Louis City Directory (1873).

[18] 1880 U.S. Census.

[19] Gould’s St. Louis City Directory (1887).

[20] Missouri Death Records (1898).

.